Learning in a New Home

“I never miss classes,” says Francisco Ariel Frandin Cribe. Each Tuesday and Thursday morning for the past five years, the 75-year-old ventured out of his home and rode Louisville’s TARC bus to KRM’s elder program in the Highlands. During these five years since he arrived in the United States through KRM’s Cuban resettlement program, Francisco has been improving his English and studying to become a U.S. citizen at the elder program.

All citizenship applicants must pass a test — in English — on U.S. history and civics. Some older applicants who are unable to learn English due to age or health can sometimes qualify for waivers that allow them to take the test in their preferred language. Francisco was determined to try in English. He worked with tutors and mentors who helped him practice his English and study for the civics questions he would be quizzed on in his interview. Every Tuesday and Thursday, he attended the elder program. When they weren’t in a classroom, the group took field trips around the city. He says he lives quietly now. “I like the American style, way of life,” he explains. “I am able to interact with the people from here. I am constantly learning new things.”

After he arrived in Kentucky, he was joined by his two adult sons, one a chemical engineer and the other an aviation engineer. The entire family had struggled to build a life in Cuba and, later, to escape, because of their reputation for political dissidence. Originally, Francisco says, the Cuban government accused one of his brothers of rebelling against the new Cuban government. The reputation immediately impacted everyone in his family.

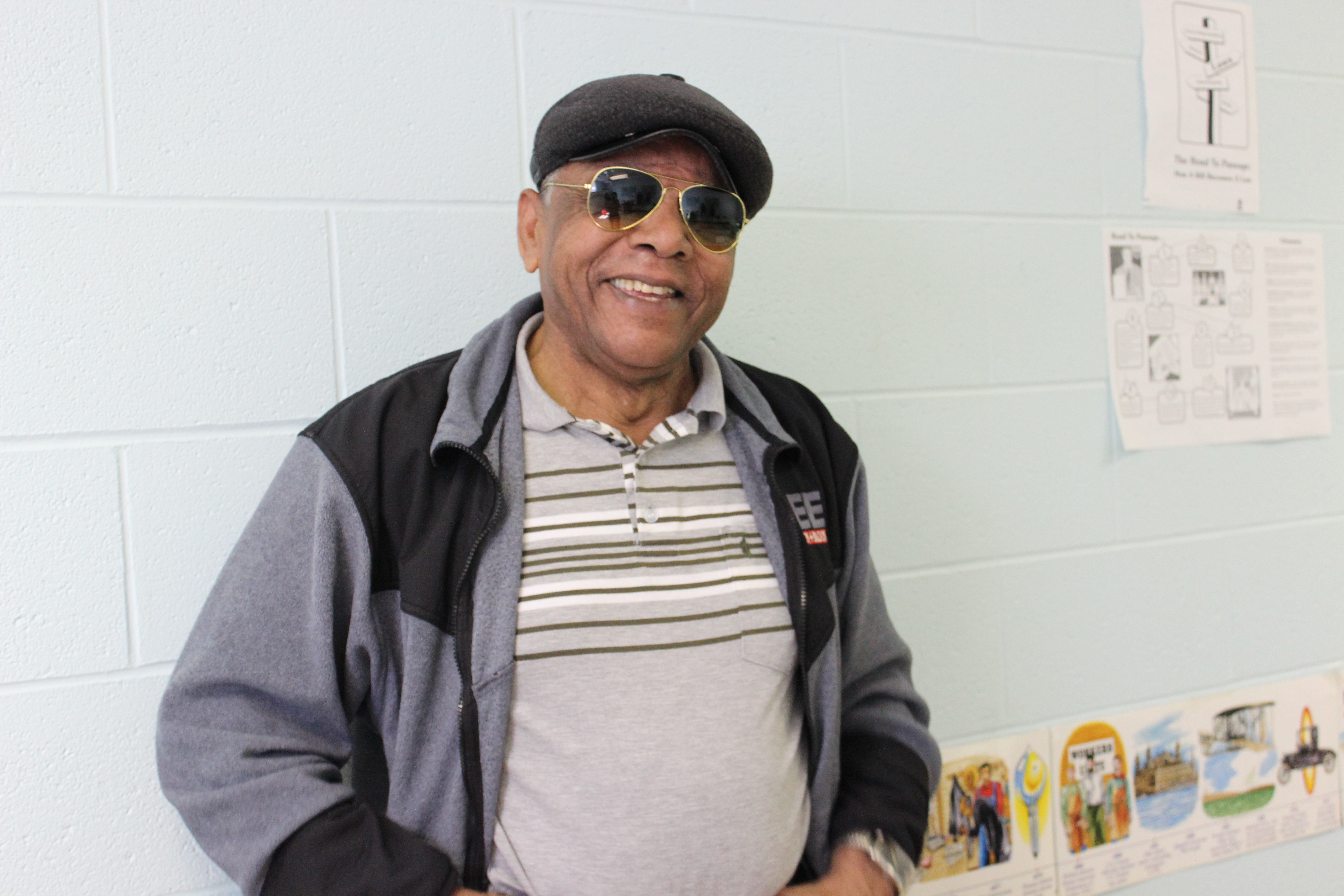

KRM staff member Yahima Nunez Leblanc with Francisco Ariel Frandin Cribe at the KRM elder program, where Francisco studied for five years.

Writing His Story In His Own Words

In 1958 during the Cuban Revolution, Francisco, 15, and his father were abducted from their home in La Maya and imprisoned. He was held captive for eight months.

As part of his U.S. citizenship application, Francisco wrote a detailed account of his captivity. He worked with a tutor from the elder program to translate the information from Spanish to English. The firsthand account is linked below.

“When you read that,” Francisco says, “you may believe it’s a story . . . something that didn’t happen. You have to go through this to know what it really feels like.”

He and his father were detained with a group of other accused rebels. Francisco was the youngest prisoner among them.

Early in his incarceration, he was led outside and told that he was about to be executed.

“I was sentenced to death by firing squad,” Francisco writes. “They took me to a field and stood me at the edge of a deep ravine. They lined up in front of me, pointed their guns at me and fired. I heard the guns discharge and then all I heard was silence.”

He was shot with pellet bullets. He lost consciousness. At the time, Francisco didn’t know what a pellet gun was and he thought he was dead.

“I was humiliated, isolated. I was an innocent teenager,” he says. “I could hear them talking, Kill him, kill him.”

“They told everybody in my town that I was dead,” he says. “My mom was searching for the body.”

Although his was a sham execution, each day Francisco saw fellow prisoners murdered by the Cuban government.

During his eight months of imprisonment, the prisoners were moved to various locations, often separated from each other and unable to communicate.

“On January 12, 1959, they took 72 people– and they killed them,” he says. “I want everybody to know what’s been happening. I was there. I lived that.” He eyes begin to water during this explanation, and he apologizes for his tears.

“They were tortured, humiliated, and shackled together like animals,” he writes in his account. “They were herded together, with their wrists tied together, so that they could barely walk. Then they were summarily executed at midnight. By dawn their dead bodies covered the hill of San Juan.”

In May 1959, he was released but forced to leave his father behind. It took months before his father, too, was released.

A Lasting Impact

During his imprisonment, Francisco’s family home and property were ransacked. He reunited with his mother, but their family became impoverished. He was able to rebuild, marry, and have children, however his family continued to struggle to find peace and safety in Cuba.

Francisco’s brother who was originally accused of being a dissident was later incarcerated for 12 years.

“When the pope went to Cuba in 1998 – John Paul II – he asked for all these people who were in jail to be released,” Francisco says. “All the dissidents and what they considered traitors, he asked for them to be released. And because the pope was asking for that, he was released.”

Later in life, one of Francisco’s sons was told he wouldn’t be able to find work in Cuba due to their family history. He fled from La Maya to Santiago de Cuba in order to find work under a different name. Upon being discovered, he again faced accusations and was later imprisoned for four months. When he was released, he faced a year of home confinement. His family helped him escape to Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and then the U.S.

Francisco’s other son served in the military and lost jobs due to his family’s reputation.

“They were saying that all of them were members of a very renowned family of dissidents and people against the revolution,” Francisco explained.

Although one son was able to have his wife and children come to the U.S., the other son is still waiting to be reunited with his family currently in Cuba.

Francisco is also waiting to reunite with his wife. His sons are helping with the process to bring her to the United States. They hope to hear news in the summer or fall of 2019.

As he finishes recounting these stories, he again asks that it be shared that 72 people died that night in 1959.

“I remember all the people, and they were murdered. . . Under a tree, they were killed.”

A Ceremony

Becoming a U.S. citizen this summer represents a dream for Francisco. “My perfect dream,” he says. “Since I was little, I always wanted to be a Marine. I wanted to but never had the opportunity.”

“The fact that we have to be in Cuba with our heads bent down, and we were always humiliated again and again, over and over. Going through all these humiliating experiences, it’s something that pushes you to this path.”

On a June day this year, Francisco dressed in a suit and journeyed to a federal building in downtown Louisville. He had passed his citizenship test earlier that month, after years of studying English at the elder program. He did not use an interpreter for his interview.

A group of KRM elder program volunteers cluster together and chat as they await the ceremony. They have all met Francisco at some point during the past five years. Some tutored him.

Everyone files into a basement meeting room. Francisco and over 70 aspiring U.S. citizens assemble in their chairs. One by one, they stand and introduce themselves and the countries they were born in: Cuba, Bhutan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nepal, Somalia, Iraq, Germany, New Zealand, Great Britain, Mexico, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Taiwan, and the Philippines.

The ceremony includes the National Anthem and a presentation of certificates. Family members snap pictures and video. Kids wave small U.S. flags. Francisco’s two sons and a granddaughter are there, beaming. Together, the group recites an Oath of Allegiance and become United States citizens.

Francisco hugs his family, the tutors, and the KRM elder program staff members. He and his children discuss lunch plans. They gather together for various photos of the group. Everyone around them, too, is posing for more pictures, capturing this day that Francisco has been waiting for– his perfect dream.

Francisco’s writings

You can read Francisco’s firsthand account of his detention. This account was written by Francisco with translation help from a KRM elder program volunteer.

Interested in learning more? Visit the pages for KRM’s elder program and naturalization classes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.